Recent Articles

Climate justice is the design challenge of our lives

Climate change and toxic emissions disproportionately affect poor and minority communities. Here’s how designers can help.

By Ellen Mitchell-Kozack, AIA, LEED BD+C, WELL AP, SEED, Chief Sustainability Officer

“The impacts of climate change will not be borne equally or fairly, between rich and poor, women and men, and older and younger generations.”

- United Nations, Sustainable Development Goals

As climate change accelerates, poor nations and disadvantaged communities are suffering the first and worst impacts. CO2 emissions associated with energy production in wealthier countries are threatening subsistence farmers in places like Uganda, where more than half have no electricity at all. Dangerous flooding in coastal areas is expected to displace 300 million people, mostly in third-world countries, by 2050. Extreme weather currently forces 26 million people into poverty each year.

With this awareness, the activism around climate change has taken on a new tone, shifting from a focus on ecological and economic impacts to a demand for social equity. Climate justice, as former president of Ireland Mary Robinson told the UN, “Insists on a shift from a discourse on greenhouse gases and melting ice caps into a civil rights movement with the people and communities most vulnerable to climate impacts at its heart.”

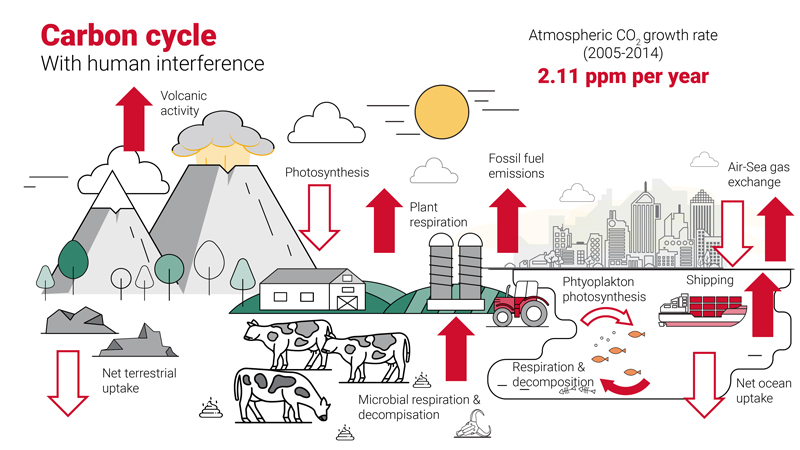

As an architect and the leader of LEO A DALY’s sustainability practice, I’ve spent my career advocating for design practices and policies aimed at eliminating greenhouse gas emissions from buildings, which together represent the largest source of atmospheric carbon in the world. Eliminating those emissions is critical for climate stability worldwide.

Today, in the spirit of climate justice, I’ll discuss some of the ways poor and minority communities in the U.S. are suffering from climate injustice. Then, I’ll talk about what we as designers can do about it.

Why the climate crisis is also a humanitarian crisis

“When your children suffer from asthma and cannot go outside to play, it is a civil rights issue.

When unprecedented weather disasters devastate the poorest neighborhoods in places like New Orleans, New Jersey, and New York, it is a civil rights issue.

When farmers in faraway lands cannot feed their families because the rains will no longer come, it is a civil rights issue.”

- Rev. Dr. Gerald Durley, Civil Rights Activist

As Rev. Dr. Durley noted, the climate crisis is also a social justice crisis. Greenhouse gas and other toxic emissions harm poor and minority communities at a greater rate than they harm more affluent areas. In the U.S., you don’t have to look far to find evidence of climate injustice playing out in our cities.

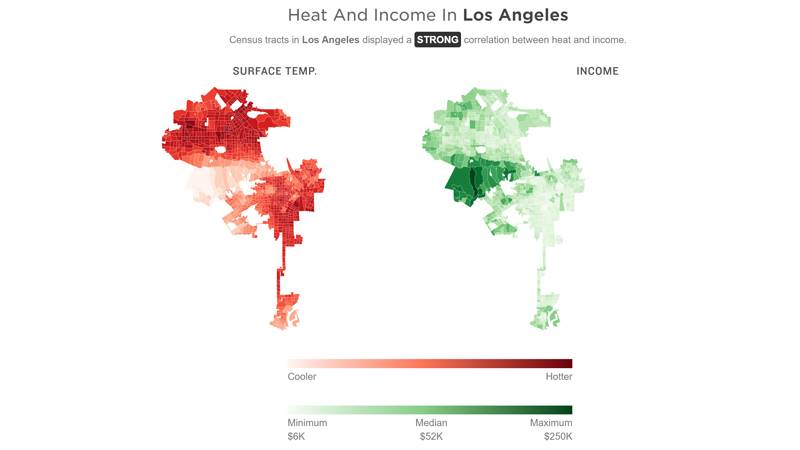

Source: NASA/U.S. Geological Survey, Census Bureau

Credit: Sean McMinn and Nick Underwood/NPR

Where it’s poorer, it’s also hotter

That’s the takeaway of a recent analysis by NPR, which compared income data in 97 U.S. cities with thermal satellite images from NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey. Temperatures in different neighborhoods within the same city can vary by 20° F. This is due to the heat island effect – localized warming that results when concrete is directly exposed to solar radiation. Heat islands are more likely to occur in poor neighborhoods, which often lack green spaces and tree canopy, where there are increased pre-existing health conditions, limited resources and elderly populations. “Regardless of where they live,” the report says, “people in poverty are more vulnerable to many chronic conditions, including some made worse by heat, like asthma and heart disease.”

Severe weather hits poor communities harder

As the climate heats up, extreme weather and natural disasters are increasing in frequency everywhere. While no community is immune to these events, their humanitarian impacts on poor communities is much more pronounced.

According to a 2020 report by the Columbia Climate School, poor communities are simultaneously more vulnerable to severe weather events, less able to withstand them, and less able to rebuild in the aftermath of a disaster. Subpar housing and old infrastructure make them more vulnerable to power outages, water issues and damage. They may lack adequate healthcare, insurance, and access to warnings in a language they can understand. They may also lack transportation to get them away from a disaster area and lack the kind of financial safety net that helps more affluent communities recover.

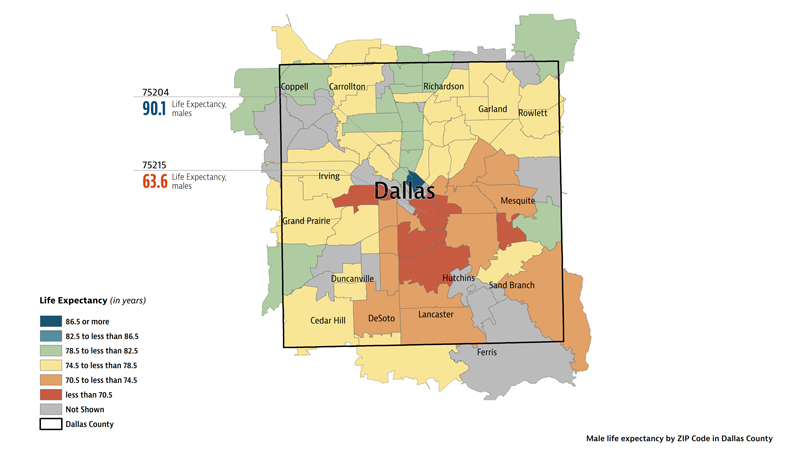

Source: The University of Texas System, UT Southwestern Medical Center, UTHealth

Toxic emissions shorten lifespans in poor neighborhoods

Living in Dallas, I’ve had the opportunity to witness firsthand the ways in which toxic emissions impact poor and minority communities disproportionately. Two local universities, UT Soutwestern and Paul Quinn College, have both been active in studying the issue, and creating reports that are publicly available and easily understood – all in an effort to educate communities about the dangers of unhealthy air quality.

UT Southwestern recently conducted a survey studying life expectancy by zip code in Dallas County, highlighting the relationship between and area’s economic conditions and its health outcomes. The results are shocking. In the West Dallas zip code of 75212 – a community that is 62 percent Hispanic and 27.4 percent Black – the life expectancy is 73 years. That’s five years less than the overall average in Dallas County, and 17 years short of the life expectancy in the 75204 zip code of Highland Park, an affluent community just four miles to the east.

This disparity can be tied in large part to the fact that industrial and manufacturing facilities are often zoned to be in and around poorer and minority communities, known as fenceline communities. Toxic emissions, some from industries directly tied to building materials, are making people in these communities sick and shortening their lifespans.

Located primarily in the southern and western sectors of Dallas, many of these fenceline communities have banded together to form The Coalition for Neighborhood Self-Determination in an effort to fight back. According to Evelyn Mayo, Urban Research Initiative Fellow at Paul Quinn College, one of the purposes of the coalition is to create land-use plans that would better separate residential areas from industry. She adds, “If the area is made up of homes, they should be treated as homes because when they’re not treated as homes, they have barriers ranging from depressed property values to inaccessible home loans to outdated infrastructure. So that’s a fair housing problem as well as an environmental justice problem.”

What can designers do about it?

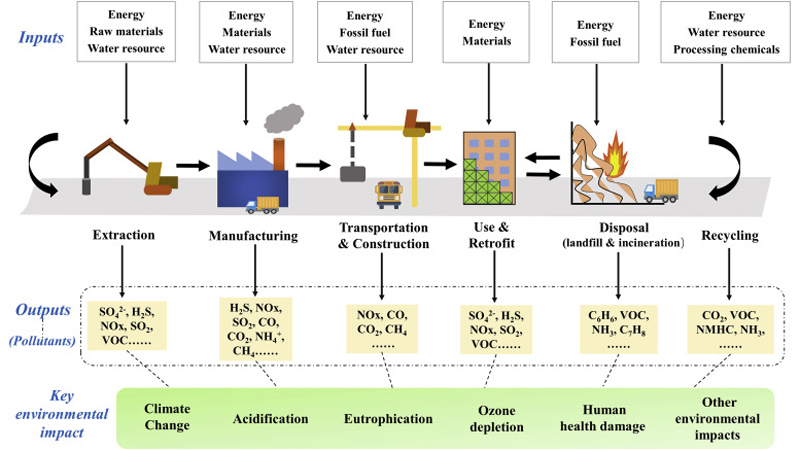

As I’ve discussed, carbon emissions and toxic chemicals associated with the built environment have real and profound social justice implications. By contributing to a rapidly warming global climate, the carbon emissions associated with the materials and operations of buildings threaten the health and resilience of poor and minority communities in the U.S. and beyond. In addition, the life cycle impacts of building materials – products we select and specify every day – can contribute to the deterioration of living conditions and health outcomes for people living in the shadows of extraction, manufacturing and waste disposal facilities.

Achieving climate justice will take an intentional and cooperative effort throughout our industry. Every designer, every design firm, and all of the clients, partners and suppliers we work with have a hand in achieving equity.

Reduce carbon emissions

Energy use in buildings produces carbon – tons of it. Approximately 28 percent of total emissions worldwide every year come from the operation of buildings. We have the tools, resources and knowledge to design our buildings to be net zero, meaning they will not consume more energy than they are able to produce. By signing on to the 2030 Commitment, we have obligated ourselves to measure, track and ultimately eliminate operational carbon emissions.

The energy used in the extraction, manufacture, and transport of building materials amounts to 11 percent of global carbon emissions known as embodied carbon. Deploying smart strategies such as reducing or replacing cement in our concrete mixes or looking for opportunities to incorporate mass timber are ways that we can draw down on our embodied carbon emissions. As noted by the Carbon Leadership Forum, “We can radically reduce carbon pollution and even store large amounts of carbon in buildings and infrastructure — permanently. But it will take millions of people demanding and creating solutions, working together in communities, simultaneously, toward one goal. We already have the innovative solutions we need. What happens next is up to us.”

Source: One World, Volume 3, Issue 5; Creative Commons – Attribution

Sign the AIA Materials Pledge

The Architecture & Design Materials Pledge is an industrywide effort to improve the ecological and human-health impacts of the materials architects and designers specify in projects. Participants commit to making more intentional product selections across their portfolios over time.

Recognizing the link between environmental and humanitarian impacts of materials, the pledge commits participating firms to

- Support human health by preferring products that support and foster life throughout their life cycles and seek to eliminate the use of hazardous substances.

- Support social health & equity by preferring products from manufacturers that secure human rights in their own operations and in their supply chains, positively impacting their workers and the communities where they operate.

- Support ecosystem health by preferring products that support and regenerate the natural air, water, and biological cycles of life through thoughtful supply chain management and restorative company practices.

- Support climate health by preferring products that reduce carbon emissions and ultimately sequester more carbon than emitted.

- Support a circular economy by reusing and improving buildings and by designing for resiliency, adaptability, disassembly, and reuse, aspiring to a zero-waste goal for global construction activities.

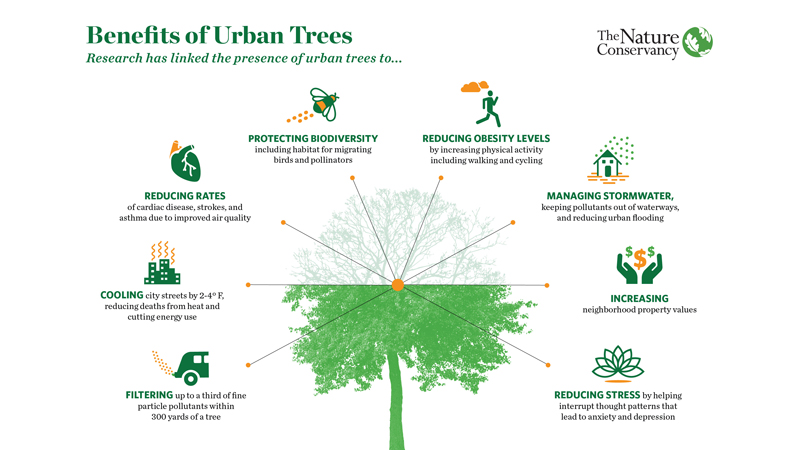

Source: The Nature Conservancy, Vermont Chapter

Eliminate heat islands

Finally, coming back to the inequities associated with extreme heat – breaking down heat islands in urban areas can make a huge difference in quality of life and health in the communities where we work.

In some ways, this is straightforward, and is oftentimes codified or at least incentivized by standards like LEED. Strategies such as designing surfaces to be reflective, increasing vegetation and planting or retaining trees. But the synergistic benefits are impressive when you add them up. Trees make a more comfortable pedestrian environment. They provide shade and thermal comfort. They help filter the air. They have biophilic benefits. They sequester carbon and emit oxygen. They enhance biodiversity. They help manage stormwater. They increase property values. And, of course, they combat the Heat Island Effect.

Selecting highly reflective building materials and landscaping our sites is something we already do, but we need to take it a step further. This includes advocating at the municipal level for the greening of lower-income communities that don’t typically benefit from real estate investment or revitalization and contributing to and partnering with non-profits that are planting trees in our communities.

Climate justice is the challenge of our era

I’ll finish with a quote from LEO A DALY President Steve Lichtenberger, AIA, from a letter he wrote introducing our firm’s 2021 Sustainability Action Plan:

“LEO A DALY is a global design firm working in a time of unprecedented change with pressures on multiple fronts – social, environmental, economic and political. Embracing the view that architecture must respond to the spirit of the age, our responsibility and our relevance lies in making the world a better place through work that responds to the challenges the era presents.”

Responding to the climate crisis, as well as to the ecological crises in our own backyards, is the defining imperative facing architects and designers today. To do this, we need to pay more than lip service to the “triple bottom line” of profit, people and planet. Rather, we need to underpin our self-concept as designers with the awareness that ecological crisis does not impact everyone equally. It disproportionately hurts the most vulnerable among us, and so requires an extra level of mindfulness, commitment to action, and a sense of urgency.

About the author

Chief Sustainability Officer Ellen Mitchell-Kozack, AIA, LEED BD+C, WELL AP, SEED leads LEO A DALY’s strategic initiatives in sustainable design, including Environmental Social & Governance, alignment with the UN Global Compact and Sustainable Development Goals, carbon footprint assessment and social impact. Ellen’s goal is to leverage LEO A DALY’s integrated design expertise to affect positive change. She applies a humanitarian and environmental lens to architecture to benefit clients, the communities we live in and the future of our planet.