Recent Articles

A young Black woman’s perspective on the architectural profession

Architectural Intern Chan’ta Hunter shares insights from her summer internship in LEO A DALY’s Dallas design studio

Here’s a fact that should startle you: In three years of studying architecture as an undergrad, I’ve met only one practicing architect who is a Black woman.

I fell in love with architecture and design as a freshman in high school. As part of an introductory course, I had the opportunity to work with a local architect on a supportive housing project for the local community. The experience showed me that I have a talent for design and a passion for making a difference through architecture.

But since I began my studies, first at Florida A&M before transferring to Prairie View A&M, the industry’s lack of diversity has been troubling. In my first year at Prairie View, a Historically Black College/University (HBCU), I was disappointed to see very few professors who looked like me in the School of Architecture. This seemed strange considering Prairie View is one of only seven HBCUs with a four-year architecture program. I have met a handful of Black architects. Of that handful, four were men, and only one was a woman. In my studies, I’ve felt like I need to do more to receive the same recognition as others in my cohort. I am proud to tell others that I am studying architecture, but I see the doubt in their eyes stemming from my appearance.

I’m a senior now, and as I wrap up my college career, my concern has grown: I do not see myself represented in this field.

This summer, I took an architectural internship in the Dallas design studio of LEO A DALY. Over the course of my internship, I’ve had the opportunity to meet Black professionals who have been generous with their time and were encouraging to me. In addition to receiving mentorship, I’ve spent time researching the history of race in architecture and used my position within the firm to gain a better understanding of how the industry is working to create a more diverse community of professionals.

In this post, I’ll share some of my takeaways. I hope to offer a perspective that I’ve come to understand is all too rare in this industry.

A call to action from 1968

The architectural profession has been grappling with issues of race, with varying degrees of success, for more than half a century. A seminal event in this effort occurred more than 50 years ago, at the 1968 annual convention of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in Portland, Oregon. The keynote speaker was Whitney M. Young Jr., a civil rights leader and executive director of the National Urban League.

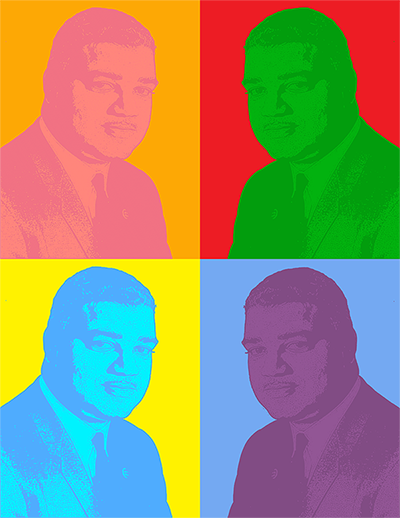

Whitney M. Young, design by Chan’ta Hunter

Young was at the forefront of the fight for racial integration and Black empowerment, and his speech at the 1968 AIA convention was a call for architects to affect change regarding the conditions Black people face in society. He gave many examples of inhumane features of the Black experience – racism that starts in the homes, prejudice as the societal norm – and he encouraged people of moral character to take a stand for equality. He said:

“As a profession, you ought to be taking stands on these kinds of things. If you don’t as architects stand up and endorse Model Cities and appropriations, if you don’t speak out for rent supplements or the housing bill calling for a million homes, if you don’t speak out for some kind of scholarship program that will enable you to consciously and deliberately seek to bring in minority people who have been discriminated against in many cases, either kept out because of your indifference or couldn’t make it—it takes seven to ten years to become an architect— then you will have done a disservice to the memory of John Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Bob Kennedy and most of all, to yourselves.”

I was particularly affected by his story about hiring a maid. Young’s wife was adamant that her family and others address the maid as Mrs. Fisher. It conveyed a sense of dignity, she said, for Mrs. Fisher to be addressed by her last name rather than the first, Lucielle, as was typical at the time. This subtle gesture spoke a profound truth about the value of the human person, regardless of their profession or skin color.

Young’s speech was significant to history because he shone a light on the pervasiveness of prejudice in America. His speech posed a challenge to the architectural profession and made it clear that courage would be necessary to effect systemic change in the education and profession of architecture.

AIA efforts toward racial justice

It has been 53 years since Young addressed the AIA convention, and the profession still has a troubling lack of diversity. According to data from the Directory of African American Architects, out of 94,000 AIA members, 2,270 are African Americans, and 452 of that number are women.

Early steps were taken in the wake of Young’s address. Immediately after the speech, AIA passed two resolutions. Resolution 10 created a national scholarship for disadvantaged minority groups, and Resolution 13 called on architects to “take a positive stand and become personally involved in the issues of our day.”

Since 1968, the representation of minorities in architecture has slowly increased. However, according to the National Organization of Minority Architects, “candidates of color are still 31 percent more likely to stop pursuing licensure.” Some progress has been made, but the challenges that prevent minorities from pursuing their licenses remain inadequately understood and addressed.

In 2015, the AIA formed the Equity in Architecture Commission. After 14 months of study, the Commission released a study, “Diversity in the Profession of Architecture,” taking a step toward understanding the problem. These efforts were expanded upon in NOMA’s 2021 report “Baseline to Belonging.” In 2020, inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, the AIA Board released a statement promising “to advance racial justice and equity in our organization, in our profession, and in our communities.” It included pledges to improve educational resources, expand inclusiveness and diversity within the profession and dismantle barriers within all AIA systems.

Diversity at LEO A DALY

Over the past summer, I was exposed to some of the results of the AIA’s efforts, filtered through the lens of one firm.

Last year, LEO A DALY launched an Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) Advisory Council with the mission “to drive change by celebrating the diverse human experience, implementing a culture of empathy and championing social responsibility.” The EDI council has influenced the launch of several initiatives in the firm. These include recruitment of interns from Historical Black Colleges and Universities (myself included), and commitment to AIA and NOMA’s 2030 Diversity Challenge to increase the number of Black licensed architects from 2% to 4% by 2030.

Through my internship, I’ve had the opportunity to meet other Black designers, both in the Dallas studio and across the U.S. I also gained a mentor, Jay Taylor, who is an alumnus of Prairie View A&M, and who introduced me to how things were done at LEO A DALY. He helped me understand how I can improve my online portfolio for architecture and digital media and gave me insight on how to use Revit according to the firm’s needs for projects. He also shared with me some of his work and helped me with infographics.

Another experience that stood out to me was meeting and spending time with Debra Crafter, LEO A DALY’s small businesses program manager and co-chair of the EDI steering committee. Throughout her career, Debra has been exposed to the role and impact of diversity in a variety of corporate and non-profit settings. Within the firm, her role is to bring about a diverse design perspective by engaging with small, minority-owned businesses, building partnerships and working with HR to develop approaches to diversity and training. Debra made it clear to me that the industry’s priorities are changing. Clients and partners today want to know how diversity is being supported at LEO A DALY.

The best advice I received from Debra was to always be my authentic self, to avoid diminishing myself, but be impactful. She encouraged me to share my perspective with others in the firm and to leave something just as I take something from my experience with the internship.

What I took away: I learned to embrace sharing my work and the areas of design that I am skilled in. You never know what you can learn by doing so, or what new opportunities can become available. I was able to make connections throughout the company and gain others’ perspectives of how they contribute to the overall design team. What I left with the firm: I gave the team insight that I can contribute as a young designer as far as a project’s storytelling and process. I advocated for the importance of pushing for diversity within the profession, from a student’s perspective as a Black woman.

I have enjoyed my experience and all the knowledge I have gained, and I hope to continue to see LEO A DALY move forward with supporting diversity and social justice within the company and in the world.

Black Females in Architecture

In an effort to better understand how I can contribute to the industry and make it more inclusive, I came across Anna Fixsen’s Architectural Digest article, “Black Females in Architecture is the IRL Social Network the Design Profession Needs.” This article opened my eyes to a resource for Black women in architecture – one I expect to be important to me as I build my career.

In the AD article, Selasi Setufe discusses her experience being “the only Black women in the room,” and how a conversation with three other women inspired the formation of Black Females in Architecture (BFA). What started as a WhatsApp thread “quickly bloomed into a full-fledged organization to support and promote Black women in the design profession.”

BFA promotes and supports Black women in the profession by coordinating workshops, meetings and book clubs to encourage those of us who are in school, as well as women in the architectural profession. They have also been actively working with larger membership-based organizations, including the AIA and Royal Institute of British Architects, to develop strategies to achieve diversity at the highest level.

I love seeing Black women in the field taking initiative to be a resource to women like myself, because it is rare to come across. Seeing a reflection of yourself or what you hope to be is very impactful.

Infographic by Chan’ta Hunter

Why it matters

Part of the reason I devoted some of my internship time to studying race in architecture is because, as I begin my career, I want to be a clear and compelling voice for change.

Here are my top three:

- Diversity creates better projects. Having a diverse profession brings about more community-minded development, where firms have more insight based on community representation.

- It makes the profession stronger. Diversity makes a career in architecture feel more attainable to those in underrepresented cultures. That influx of new perspectives also brings more creative ideas to the table.

- It pays. According to a 2012 report from McKinsey, companies in the U.S. with diverse executive boards enjoy a 95% higher return of equity compared to those with homogenous boards. That alone should be an incentive for change (beyond just plain ethical reasons).

As I prepare to graduate, I feel that society is slowly making progress with racial justice. The industry I am entering has seen change even since I started my studies at Florida A&M and Prairie View A&M. That is encouraging. But we have a long way to go.

I hope to be part of that change.

About the author

Chan’ta Hunter is an architecture major and digital media arts minor at Prairie View A&M. In summer 2021, she served as an architectural intern in LEO A DALY’s Dallas design studio.